Closing a Loophole

June 2024 Imperfect Union

On this day in 1804…three-fourths of the states ratified the 12th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

First, a bit of housekeeping. Many of you might have seen the announcement online, but just in case, I’ve accepted a new job. Starting July 22, I’ll be the Executive Director of the George Washington Presidential Library. It’s a big change, and a very unexpected one. But it was an opportunity I simply could not pass up and I’m very excited for this new chapter.

I’ll still write this newsletter, do a book tour, and write about presidential history - so hopefully not much will change for you. Except that I’ll have even more cool stuff and experiences to share!

Second, in case you missed it last month, I’ve launched my pre-order campaign. I’m working with Porchlight to offer signed copies with a 30% discount. Every copy will received a signed book with this custom, Adams-themed bookplate.

You will also see on the page that there are a number of bonus offerings for bulk purchases. Book recommendations, custom art prints, and an exclusive e-book offering are all available depending on the size of the order. The goal is to encourage groups of readers, whether they be book clubs, DAR chapters, boards of organizations, or friends to pre-order and to thank them with extra goodies. This offer is only good through August 22, 2024.

Ok, thanks for your patience. On to history!

On September 4, 1787, the delegates at the Constitutional Convention had been meeting for over three months. They were hot, tired, grouchy, and eager to return home. And yet, much of the presidency was still up in the air.

The Committee of Eleven (creatively named for the eleven members) was tasked with sorting out many of the remaining executive details. On September 4, they proposed the Electoral College as a method to elect the president. It allowed for a popular vote without leaving the choice directly to the whims of the mob.

Yes, you read that correctly. The delegates didn’t discuss the electoral college until September 4. Then, within the next few days, the delegates also settled on the treaty-making responsibilities, the right to appoint lower officials, and the four year term (with the possibility of reelection).

In many ways, the presidency was an afterthought. Or at least, the parameters and specifics of the presidency. The concept had been debated for years and the delegates had become increasingly comfortable with concentrated executive power over the last decade through the challenges of the war and the Confederation period. But once they finally got down to business and hammered out the details, they did a lot very, very quickly.

Many of their choices, including the Electoral College and how the president and vice president would be elected, were last-minute creations. Which is not to say some of their creations weren’t brilliant - many were ingenious. Others had excellent intentions, but didn’t quite work out.

The delegates were wise enough to know their weaknesses and own human fallibility. Accordingly, they anticipated that there were challenges they couldn’t anticipate and/or that some of their creations wouldn’t work. Hence, Article V of the Constitution, which gave Congress the right to pass amendments. A two-thirds vote is required to pass the amendment in Congress, followed by three-quarters ratification of the states.

Congress quickly put these powers to the test in the summer of 1789 when it passed the first ten amendments, known as the Bill of Rights.

Another big test came in 1800. As many of you know (or have heard me discuss or will, this election will be a big topic this year), Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr tied in the election of 1800. That was possible because Article II instructed electors to cast two votes, one for a candidate outside their home state, but did not specify that one vote had to be for a vice presidential candidate.

The system was quite lovely in principle. Parties had not yet emerged and the goal was for the electors to pick the two best qualified candidates. They also anticipated that candidates would regularly fail to win a majority (after George Washington), and thus the election would frequently go to the House.

After the first two elections, it was clear this expectation had not come to fruition. In January 1797, one congressman submitted a proposal on the House floor to amend the electoral process in the Constitution. His resolution went nowhere.

Three years later, that failure to take action came back in a big way. By 1800, parties were on the rise and the Democratic-Republican caucus had clearly designated Thomas Jefferson as the presidential candidate and Aaron Burr as the vice-presidential candidate. While the tie was not improper, it was not the voters’ intentions. That’s often the crux of constitutional crises - do you follow the strict letter of the Constitution or the will of the people?

The final chapters of Making the Presidency tackle this election, the resolution, and the all-important transition. To avoid repetition, I’m going to skip past that for now.

Many who lived through the election, the contested results, and the transition felt that the republic had barely survived and they were keen to prevent a similar crisis in the future. The New York state legislature began debating amendments to their own state process almost immediately. DeWitt Clinton, a leading voice for the reform in New York, won a vacant seat in the US Senate, and brought the discussion to Congress.

Democratic-Republicans agreed to table the issue until the 1803 session because they would have a larger majority and an easier time securing the two-third vote required. On October 17, the first day of the 1803 session, they introduced the amendment for debate in the House. Just a few days later, the Senate started its own deliberation.

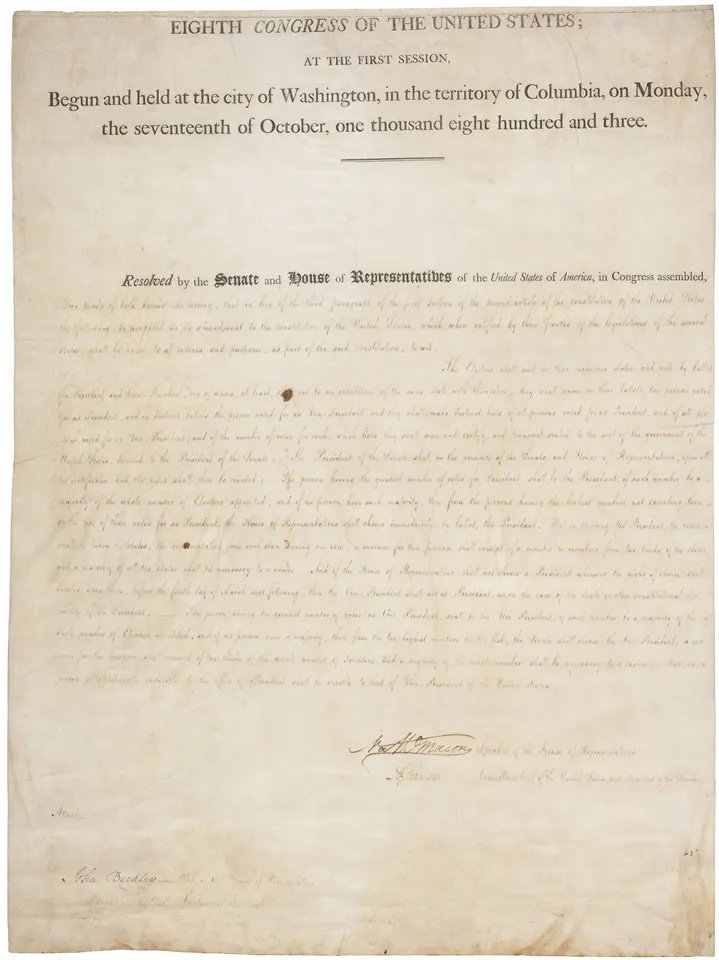

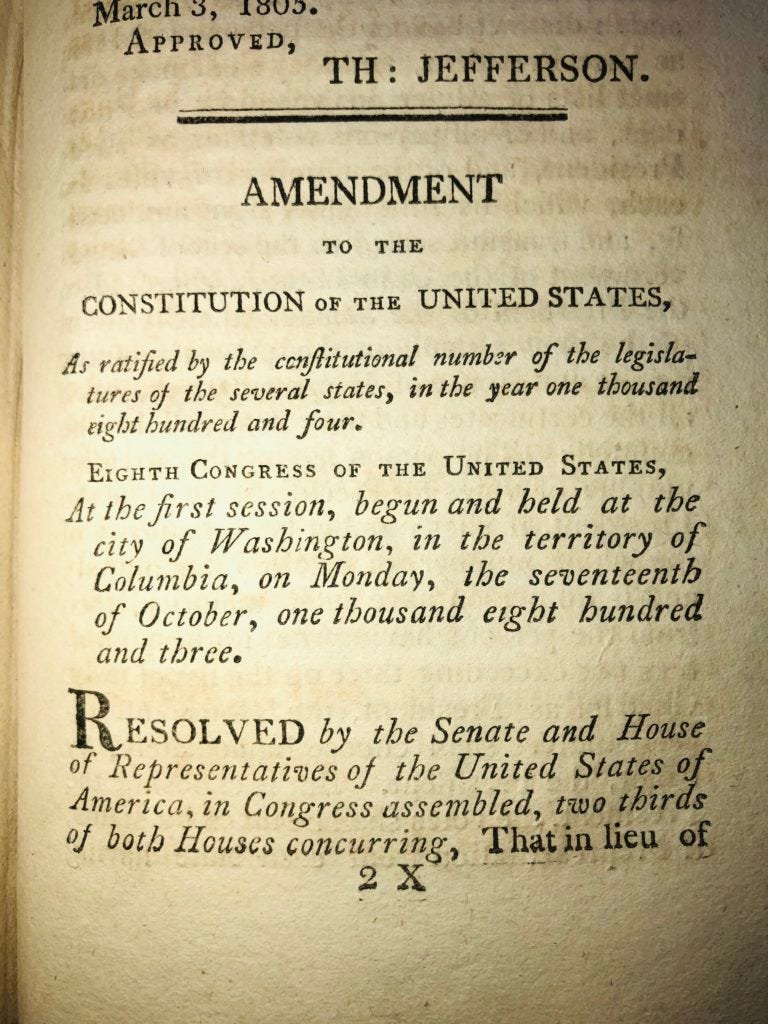

On December 3, 1803 - just three years after Jefferson, Adams, and Congress discovered the tie vote - Congress passed an amendment changing how presidents and vice presidents get selected. It would have passed a few days earlier, but the Democratic-Republicans were waiting for all of their members to arrive. Three days after passing the bill, Congress submitted it to the states.

courtesy of the National Archives

North Carolina was the first state to ratify the amendment on December 22, 1803. New Hampshire was the fourteenth (the key state) on June 15, 1804. An interesting parallel, as New Hampshire was the key state to ratify the Constitution as well. Fun fact - Massachusetts rejected the amendment and didn’t get around to ratifying it until 1961.

On September 25, 1804, Secretary of State James Madison declared the 12th Amendment officially part of the Constitution. Just in time for another presidential election.

Typing out those dates, and the progress of the legislation through Congress and then the states, I am blown away by the speed. Keep in mind, all of their correspondence and communication could only travel as fast as a horse could run or a ship could sail. And yet, in just three years (including many lengthy congressional recesses), they had passed an all-important constitutional amendment to prevent a similar threat to the republic.

The Electoral College is far from perfect (let me list the imperfections!), but I think it is inspiring that rapid and coordinated action was once possible.

Books:

Just a reminder: I haven’t read (or haven’t finished) the books below. They’ve caught my eye, but I’m not necessarily vouching for them. I share published reviews in the links below (as well as on Goodreads and in my Instagram stories - see book review highlights).

Because of everything in the last month, my reading is a little slow. Repeating a few in case you are behind too!

Currently Reading: American Covenant: How the Constitution Unified Our Nation―and Could Again by Yuval Levin (June 11, 2024)

Up Next: Autocracy, Inc. by Anne Applebaum (July 23, 2024)

Coming Soon: Against Constitutional Originalism: A Historical Critique by Jonathan Gienapp (September 3, 2024)

On the Horizon: Reagan: His Life and Legend by Max Boot (September 10, 2024)