Gerrymandering: Then and Now

November 2022 Imperfect Union

Before I turn to the substance of today’s article, I wanted to thank you all for being here. As most of you probably know, Twitter is a bit of a hot mess at the moment. While I’ve never put all my online eggs in one basket, the platform has done a lot of good things for me. I’ve met a lot of you, I’ve discovered brilliant people, I’ve learned a ton, and it remains the best place to follow journalists and experts. I’m still hoping it can be salvaged, but I’m also trying to think strategically about what to do if it truly disintegrates.

One answer is a more robust Substack presence. The platform is currently rolling out a new chat feature, which is really more like a Facebook or Instagram post rather than a direct message option. It’s only available on the Apple app for the moment, but as soon as they release the Android app, I might make it available. To be clear, that won’t change my newsletter at all. You will not be spammed by chat messages, promise! But if you are interested in more engagement or used Twitter, it might be a good alternative. I’ll keep you posted. Another option might be a weekly quick hits post – sort of a collection of the things I would say on Twitter, but in one weekly post. Less essay, more bullet points. Again, this offering would be optional.

I’d also welcome your feedback. Where do you like to get information? Would you like a bigger Substack offering? Is another platform your preference? I’d genuinely like to know. Feel free to reply to this email or you can comment below.

Ok with business out of the way, time to turn to history. Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the last week, you know that we just had midterm elections. Regardless of party, I will say that I’m delighted that election denier candidates lost. That’s just good for the country and our institutions. However, one of the disheartening aspects of last week was seeing how few districts are actually competitive.

There are two reasons for this development. First, Americans are self-sorting based on partisan preference. If you are an ardent Republican, living in San Francisco might be less appealing than a rural district. Similarly, if you a liberal Democrat, living in rural Arkansas might not work for you. Both of these hypotheticals assume, of course, that you have a choice and the means to move.

The second reason is the rise of gerrymandering. Gerrymandering isn’t new, but it has been through a few distinct phases since its inception in the early 19th century. I’ll walk you through the four phases of gerrymandering and then offer a few suggestions about what we can do about it.

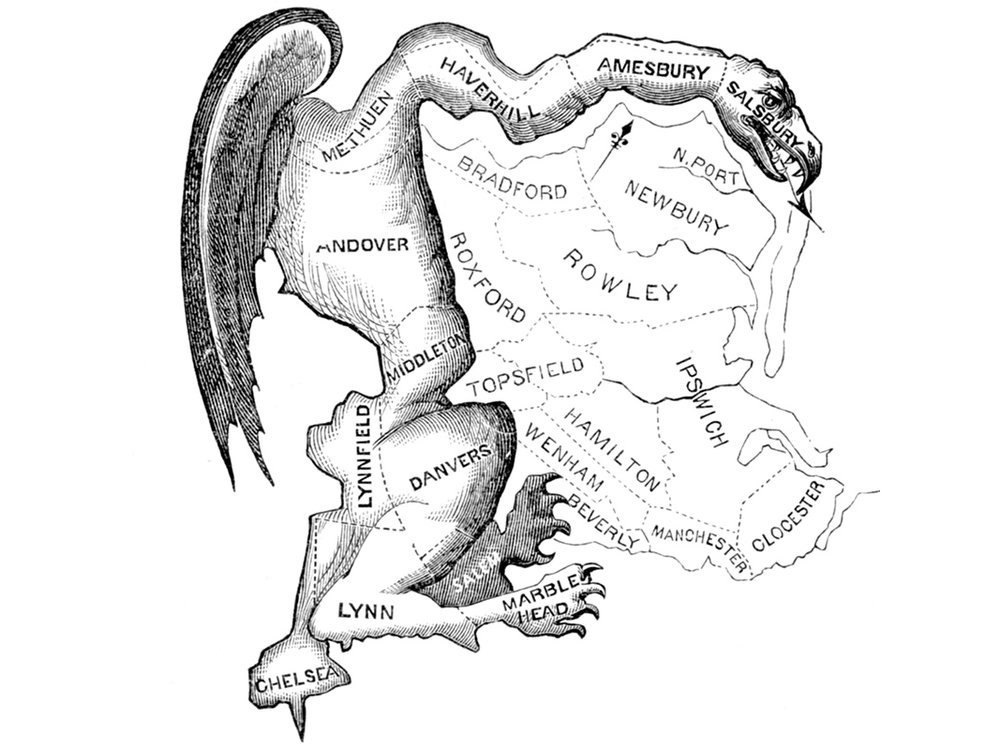

Although Massachusetts is a reliably Democratic state these days, it used to be ground zero for partisan battles. In 1812, Democratic-Republicans (also sometimes called Jeffersonian Republicans or just Republicans) were had a majority in the state legislature and a Democratic-Republican governor, Elbridge Gerry. However, they knew that Federalists would likely gain more votes in the coming elections because the War of 1812 and the accompanying economic embargo were very unpopular in the state. To gain more seats, the legislature crafted a district map to split Federalist votes. One of the districts was particularly ridiculous, as you can see in the image below. Despite the overt political intentions, Governor Elbridge Gerry, signed the legislation into law.

Elkanah Tisdale, a cartoonist, drew the district as a winged salamander to poke fun at the absurd borders. Richard Alsop, a poet and regular Tisdale collaborator, dubbed the district lines a “Gerry-mander” and condemned “many fiery ebullitions of party spirit, many explosions of democratic wrath and fulminations of gubernatorial vengeance within the year past.”

(One quick note, Gerry was pronounced like Gary, rather than Jerry. So really it should be pronounced Gary-mandering.) The cartoon and Alsop’s denunciation of “The Gerry-mander” was published in the Boston Gazette on March 26, 1812.

The gambit worked. The Federalists received more votes statewide, but the Democratic-Republicans were allocated more seats in the state senate. Unfortunately for Gerry, however, the term stuck. H.L. Mencken’s The American Language dictionary included “gerrymander” as early as the 1820s. The term didn’t enter Webster’s Dictionary until 1864. According to Mencken, Webster omitted the term because his family was friendly with Gerry’s widow. The evidence of that claim is a little shaky, but it would be pretty funny if true.

Gerrymandering is possible because the Constitution requires relatively equal representation between each district and regular reshuffling every ten years to ensure this parity exists. Now, the parity isn’t perfect. Rhode Island’s Second District has 543,688 residents and Montana’s first district has 1,104,271. So that’s obviously not ideal, but the goal is try and keep them relatively even. For example, in the most recent census redistricting, California lost a district, while Florida gained one.

That process is good and appropriate and normal. The politicization of this process is the challenge. As demonstrated by the first instance, the goal is to “crack” the voting base of your opponent and “pack” your voting base. Let me give an example of how this works today. Let’s say a state is relatively split 50-50 in a state. But the Democratic voters tend to be congregated around urban centers and Republican voters tend to be concentrated in the rural areas. If the state draws the districts such that a small bit of the city is in several districts, those Democratic voters might only make up 20-30% of the vote in that district and not enough to elect a Democratic representative. The Democratic vote would then be “cracked” between several districts, while Republican voters would be “packed” such that they would have a majority in that district.

I used the terms this way as an example, but both parties are guilty of gerrymandering at both the state and federal level.

The first phase of gerrymandering lasted from about 1800 to 1870. Because only white men were considered citizens, gerrymandering wasn’t always motivated by race (although ethnicities, like Irish and Italian were definitely considered in cities with large immigrant populations). Instead, the goal was to dilute one party’s votes and boost the other.

The end of the Civil War and the passage of the 14th and 15th amendments ushered in the second phase and the introduction of race as a gerrymandering consideration. After a brief period of Reconstruction and Black electoral success, many states began to pass Jim Crow laws that limited the ability of Black men to exercise their right to vote. Just a reminder, white women gained the right to vote in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th amendment. After 1920, black women “technically” could vote, but were largely disenfranchised through the same Jim Crow laws that had targeted Black men decades earlier. Where states hadn’t passed Jim Crow laws, the legislature often factored race into the district design process.

The third phase commenced with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Voting Rights Act prohibited racial gerrymandering and established several protections against this practice. The Voting Rights Act required states with a history of depriving voters of the franchise based on race to submit proposed changes to the Department of Justice for review. This provision largely applied to southern states, but also Arizona, as well as several counties in California, New York, and South Dakota.

In 1986, the Supreme Court provided further clarification. In the case, Thornburg v. Gingles, the court established criteria to prove a gerrymandered map was based on race.

“The minority group must be able to demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geographically compact to constitute a majority in a single-member district.”

“The minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive.”

“The minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”

If these conditions were met, the map must be thrown out and the state had to begin anew. The Court also interpreted the law to create majority-minority districts, to ensure that minorities had representation in Congress. Sometimes these districts looked gerrymandered in a bad way because they are rarely “compact.” But the law worked as intended. It produced much more diversity in Congress and by 2015 had created 122 minority-majority districts of the 435 districts.

The fourth phase, where we currently are now, began in 2013 when the Supreme Court began undermining the Voting Rights Act. The majority opinion declared that states no longer needed to submit proposed changes to their voting process to Congress for approval. They argued that the country was not the same as it had been in 1965 and the protections were no longer required. The dissent, authored by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg included one of the most cited lines. Ginsburg said,

“throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

The Court further removed itself as an arbiter of gerrymander in 2019, when Chief Justice John Roberts declared in Rucho v. Common Cause, “Partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.” He further explained,

“Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions.”

Since then, federal judges have attempted to strike down gerrymandered maps that were drawn with clear partisan intent, but on appeal those judges have been overruled. Just this year, a federal judge struck down a proposed map in Alabama, arguing that the map was clearly designed to dilute the Black vote:

“The court’s opinion found that the evidence of racially polarized voting in the Black Belt was stark — on average, only around 15 percent of white voters in the region are willing to support the same candidates as the Black community.”

The Supreme Court issued a stay—basically leaving the map in place—saying that it was too close to the election. The arguments were heard on October 4.

For what it’s worth, if the stay hadn’t been issued, Alabama would have likely had another Democratic representative. As we await final vote tallies to determine the leadership of the House, that extra seat might have had a pretty significant impact.

So that’s all the bad news. Gerrymandering is here in full force and has an immediate and noticeable effect. Because the Supreme Court has eliminated itself as an umpire on this issue, we must look to other solutions.

First, Congress could pass another Voting Rights Act that forcefully addresses gerrymandering. There are two problems with this approach. First, the Supreme Court ruled against Section 2 of the 1965 bill because it was based on 1965 conditions. In theory, that same logic wouldn’t apply if the new bill focused on current conditions. But my confidence in the Court is pretty low right now. I have zero faith they’d follow the precedent they themselves established just a few years ago. This method, therefore, wouldn’t necessarily be foolproof, but it is an option. Second, there isn’t much appetite in Congress to eliminate gerrymandering because both parties want to use it. It’s the same reason term limits in Congress are unlikely to pass—neither party wants to limit themselves in the future.

The second option is more hopeful. Some states have started drawing their maps using an independent commission composed of non-partisan members. Bipartisan commissions don’t work because both sides try and entrench their own districts and their own members. But nonpartisan commissions have demonstrated that they can create fair and equitable maps that accurately represent the voters in their states.

Most recently, Michigan voters approved an independent commission to draw a new map. The commission solicited proposals, heard from experts, and underwent a lengthy process to create a new map. It’s not perfect—no map will be—but election experts largely agree that the map does a good job ensuring voters are heard and represented fairly. That’s a fantastic outcome.

Ideally, we should push for both solutions. Congressional action and state independent commissions would have the biggest impact on our elections. But if federal action isn’t available right now, you can urge your state to adopt changes at the local level. Every bit matters.

It occurs to me as I’m wrapping up this essay, that I never clearly articulated why I think gerrymandering is bad on principle. Sure, it’s nice when your party has a clean sweep of a state or a region. I’ll admit to enjoying that advantage as much as the next person. But I believe our system would work better if politicians had to really work for our votes, rather taking certain ones for granted. I think they would be more responsive to voter concerns and more likely to take action. Citizens would also be more incentivized to participate. Cynicism about the government would be lower. That is an admirable goal.

Perhaps more importantly, I fundamentally believe that each citizen should have the right to vote. And they should have faith that their vote matters and will be heard. Gerrymandering makes certain votes count as less than others and effectively silences certain citizens. I’m not ok with that. I hope you aren’t either.