Keep Your Enemies Close

April 2025 Imperfect Union

Before I get to the meat of this newsletter, I wanted to share an update about a new podcast. As part of my job as Executive Director of the George Washington Presidential Library, I am hosting a podcast called Leadership & Legacy: Conversations at the George Washington Presidential Library. I interview historians about leaders in the past or people in current leadership positions who have interesting insights to share. There are history podcasts, there are leadership podcasts—this one aims to create a unique overlap between the two. I’m having a really great time with it and I hope you’ll check it out. The podcast is available wherever you like to listen!

Ok, on to the history. The Alien Enemies Act of 1798 has been in the news lately, as it is the current legal basis being used for deporting immigrants. If you’ve read my recent book, Making the Presidency, this bill will be familiar to you. [Signed copies always available at Politics & Prose]. I will confess that I did not expect this part of the book to be in the news. I thought it far more likely the Sedition Act would be relevant. But here we are and I thought it would be helpful to offer a bit more historical context, how the bill has been used in U.S. history, and why it matters. There have been a lot of great articles on the bill, but I think many are missing the context of 1798, the original intent of the bill, and its public reception. These things matter a great deal to our current interpretation.

The Alien Enemies Act was part of what is known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. That umbrella term actually refers to several bills passed in the summer of 1798. Relations between the United States and France had been frosty for several years, and the tensions accelerated as President John Adams took office in 1797. French privateers regularly captured American ships, imprisoned American sailors, and sold off American goods and kept the proceeds. Adams dispatched a three-man diplomatic mission to Paris to resolve the tensions, but the mission went awry. The American envoys were met with hostility, and demands for bribes, embarrassing apologies, and loans that would drag the United States into war with Great Britain. When French demands were rebuffed, the American envoys were kicked out of France.

Word of this treatment reached Philadelphia in the spring of 1798 and provoked immediate outrage. Americans were furious at the insult to their sovereignty and many were convinced a French declaration of war would arrive on the next ship into port. To prepare for the possibility of war, Congress passed several bills increasing the size of the army, creating the naval department, and expanding the navy. Congress also passed four bills addressing the possibility of violence at home—the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Two important political developments fueled the fears of domestic instability. First, tens of thousands of French citizens had fled the French and Haitian Revolutions and sought refuge in cities like Philadelphia. Many Americans feared that these French nationals remained loyal to their motherland and would aide the French army in the event of an invasion. Second, partisan tensions had devolved over the past several years and the animosity between the Federalists and Republicans was fierce. (Note: they called themselves the Republicans, but are often described as the Democratic-Republicans or Jeffersonian Republicans. They should not be confused with the Republican Party of Lincoln, Reagan, or today). Partisans regularly brawled in the streets, responding to calls by partisan newspaper editors for violence, and beating their partisan opponents in return. Partisan militias comprised of ethnic immigrants paroled the streets and death threats were regularly delivered to federal officials long before the Secret Service protected the president.

The fears were real and genuine, but they were used and perverted for partisan purposes to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, which consisted of the following bills:

Naturalization Act: The Naturalization Act amended the existing bill on the books and made it harder to become a citizen. The Federalists in Congress pushed through this bill because immigrants tended to vote for Republicans and they aimed to undercut this support. The bill put onerous restrictions on naturalization, including requirements that any potential citizen,

“shall have declared his intention to become a citizen of the United States, five years, at least, before his admission, and shall, at the time of his application to be admitted, declare and prove, to the satisfaction of the court having jurisdiction in the case, that he has resided within the United States fourteen years, at least, and within the state or territory where, or for which such court is at the time held, five years, at least.”

The likelihood that immigrants would have the foresight or remember to declare their intentions five years before the appropriate time, and also to remain the same state for five years was low.

Sedition Act: The Sedition Act made it a crime to criticize the president or Congress. It notably left off Vice President Thomas Jefferson (a Republican) and expired at the end of President Adams’s term. It was passed on a partisan vote. Two important caveats to this bill: 1) The fears that motivated the bill were genuine and well-founded. There were no restrictions on First Amendment speech at the time (today courts acknowledge that speech intended to provoke violence is not protected by the First Amendment). 2) It was intensely political and designed to crush the Republican Party.

Alien Friends Act: The Alien Friends Act was a radical bill, crammed through Congress by the extreme wing of the Federalist Party. It gave the president almost unilateral authority to deport foreign nationals at will, and it offered no protections to suspected aliens. While President Adams signed the bill, he never used the enormous authority granted to him.

Alien Enemies Act: The Alien Enemies Act is in effect,

“whenever there shall be a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion shall be perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States, by any foreign nation or government.”

Those are pretty specific terms limiting when this bill is in operation. It requires a declaration of war or an invasion by the armed forces of a foreign nation or government. Sometimes bills can be vague. This is not one of those times.

The bill then provides a series of protections for suspected aliens. First,

“Provided, that aliens resident within the United States, who shall become liable as enemies, in the manner aforesaid, and who shall not be chargeable with actual hostility, or other crime against the public safety, shall be allowed, for the recovery, disposal, and removal of their goods and effects, and for their departure.”

In other words, if the alien enemy hasn’t done anything wrong, then they have to be given a reasonable amount of time to leave the country. Additionally, the bill requires that any alien apprehended must be brought before a “judge or justice” and offered,

“a full examination and hearing on such complaint.”

If, and only if, “sufficient cause” is presented during the hearing, then,

“such alien or aliens to be removed out of the territory of the United States.”

This bill was actually introduced by Republicans in Congress to try and forestall the more radical Alien Friends Act. These efforts failed, as the Alien Friends Act passed anyway. The Alien Enemies Act passed with a widespread bipartisan vote.

That vote is important because it reveals that congressmen in both parties viewed the bill as a reasonable war measure. The bill was reasonable because it included two protections.

It included all three branches in the process. Congress had to declare war. The president had to issue a proclamation and begin proceedings. Then the judicial branch had to conduct hearings. It would be much harder for one party to force abuses through three branches.

It provided suspected alien enemies with appropriate due process and the opportunity to defend themselves.

The bill is still on the books and has been invoked three times.

War of 1812

In July 1812, Secretary of State James Monroe issued a circular declaring that “all the subjects of His Britannic Majesty, residing within the United States, have become alien enemies.” The Madison administration required British citizens move 40 miles from the coast, instructing them to leave cities including Boston, New York and Washington.

Much of the historical record of Madison’s use of this bill is missing—perhaps because Washington, D.C. and the executive department offices were burned by British troops. Apparently, even the president’s public proclamation can’t be found, according to Katherine Yon Ebright, a lawyer at the Brennan Center for Justice and an expert on the Alien Enemies Act.

But Chief Justice John Marshall’s ruling exists, which ordered the release of a British immigrant. The ruling said the law should not have applied to immigrants who had not been instructed to relocate.

World War I

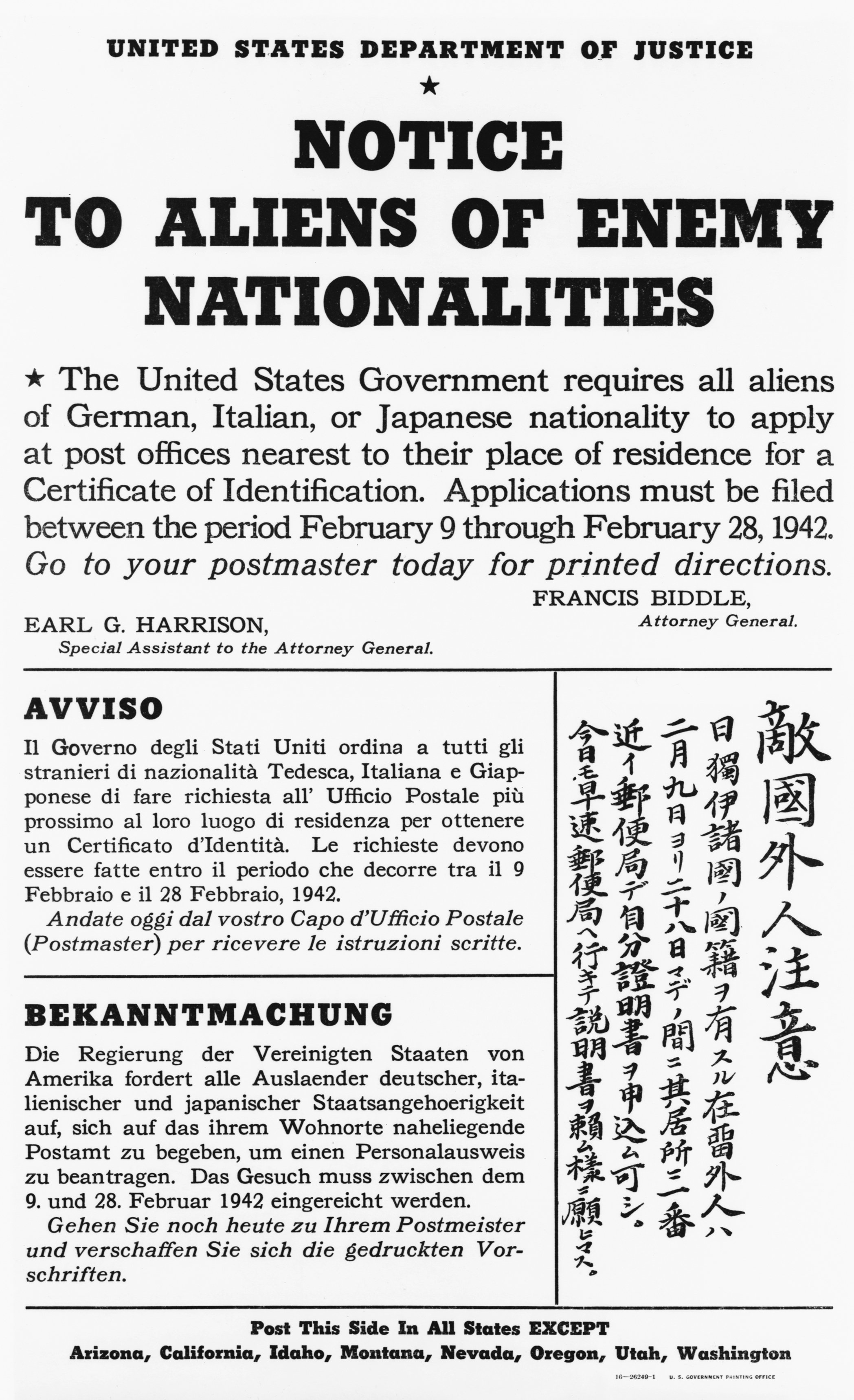

The Wilson administration invoked the Alien Enemies Act from the early days of American participation in World War I. The proclamation required German immigrants age 14 or older “to be entered into a registry, photographed, fingerprinted and, in some cases, detained.” As the war continued, these regulations were extended to include German Austrians and women of both nationalities. Alien enemies were prohibited from entering sensitive areas, required to register with the police or US postmasters, and restricted from owning signaling devices, radios, and firearms. German nationals were often subject to surveillance. More than 10,000 were arrested and investigated, even if most were paroled.

World War II

World War II witnessed the most infamous use of the Alien Enemy Act. About 120,000 Japanese Americans were relocated and forcibly interned in camps away from the West Coast. Unlike the War of 1812 and WWI, Japanese internment specifically targeted Japanese-Americans. They were citizens, not foreign nationals. The internment was upheld by the Supreme Court in Korematsu v. United States. In a dissent, Justice Jackson delivered a warning that the decision would “lie about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that c[ould] bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

In 2018, Justice John Roberts wrote in the majority decision in Trump v. Hawaii, that “Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—“has no place in law under the Constitution.”

I am not a lawyer, nor am I a judge. So I will leave most of the analytical work to them. But I will say this. No war has been declared on a foreign government. No foreign government has invaded the United States. The gang used to justify the use of the bill has been explicitly decried by the Venezuelan government and our intelligence agencies have determined there is no link between the two. Usually original intent requires some mental gymnastics, but in this case the original intent of the bill could not be more explicit. Given that the bill is still on the books, I’d think that original intent would apply.