Soft Power

March 2025 Imperfect Union

You’ve probably heard the words “soft power” being thrown around a lot lately. It can sound a bit wonky; something that is discussed in hallways of college buildings after political science classes or the academic debates in the text of foreign policy journals. But it’s critically important. The world is a big, chaotic place and soft power is in our best interest to cultivate—and it always has been. That’s the part of the story that isn’t always told. I thought it would be helpful to explain what soft power is, how it works, why it matters, and critically, where it started.

Soft power comes from the basic acknowledgement that we can’t enforce our will through military might everywhere. Massive empires have largely expired. Self-sovereignty is now an expectation, even if imperfectly applied in practice. People want a say in how they are governed. Even if we rejected self-sovereignty, Americans don’t have the interest or will power to place boots on the ground around the globe.

If you can’t force people to do what you want, can you pay them to do it? Sometimes that works, and sometimes we do. But it is limited in practice and very, very expensive. On occasion, Americans also find it distasteful when we buy people off. So what’s left?

In the 1980s, political scientist Joseph Nye made famous the term “soft power.” Nye defined soft power as the ability to influence the behavior of others to get the outcomes you want. Hard power is through coercion and/or military force. Soft power can be understood in lots of ways, but it’s basically everything else. Convincing people to do what you want, whether it be by the power of example, the appeal of an argument or culture, or building goodwill.

Perhaps the most famous example of soft power is the Marshall Plan. In 1947, most European nations were left in ruins after the war, their economies were shattered, and their people were teetering on the brink of famine. The Soviet Union was on the march from the east, and the threat of communist expansion was real.

Secretary of State George Marshall proposed a large-scale economic redevelopment plan to rebuild European economies, which would stabilize their governments and foster long-term trade partnerships. in 1948, Congress passed a bill closely following Marshall’s suggestions. Over the next four years, Congress appropriated $13.3 billion for European recovery.

European economies recovered, experienced unprecedented rates of growth and agricultural production, and developed integrated trade relationships. Scholars debate whether the Marshall Plan initiated this recovery or simply accelerated it, but I think there is little doubt that it was a smashing success.

Now, you could make the argument that the U.S. had the moral duty to offer the Marshall Plan. It was the only major economy left standing after the war and we owed our friends and allies assistance. But moral obligations rarely get far in foreign policy.

The Marshall Plan served our best interests. After the American war, our economy shifted from war production back to mostly consumer production, but at much larger scale than pre-war levels. European markets, on the road to recovery, were eager consumers of American goods, which produced money for American business and supplied jobs to soldiers returning from war.

In the post-war era, most western European nations largely deferred their national security to the United States. They remained under the American nuclear bubble and outsourced foreign policy decisions to the U.S. Not always, of course, but generally. We shared intelligence with allies and they shared it with us. That meant we had to obtain fewer sources ourselves and put fewer American boots on the ground. They also cultivated different specialties, which supplemented our own knowledge and reduced our need to master every region and source material. (Today we often refer to this sharing agreement as the Five Eyes. It included the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Great Britain).

As a result, when the U.S. took a foreign policy position, from roughly 1945 to the early 2000s, our allies went along with it. There were some fractures during the War on Terror, and rightly so. But even with our massive blunder in Iraq, allies still wanted to work with us and that’s because of soft power.

Soft power is not quite the same as a pure alliance. Under the terms of an alliance, the parties are obligated to take certain actions. But soft power can help—allies are more likely to want to help if they like you. Here are some of the ways soft power has benefited the United States.

American society had great appeal. Companies wanted to invest in the U.S. because our society has been reliable and based on the rule of law. The rule of law is critical for businesses because they can trust that contracts will be respected and enforced. Our banks don’t fail unexpectedly and the level of corruption is (relatively) low. These conditions encourage financial investment. Scientists, entrepreneurs, and talent wanted to come here because they wanted to attend our universities, perform in our venues, and share product with our very wealthy consumer base. That brings in money and talent—two things any nation wants.

The appeal of our culture strengthens American businesses and provides jobs to Americans. Have you ever traveled across the world to see someone in Nikes or a Kobe jersey? Disneyland Paris is a thing and not just Americans visit it. Those American businesses employ American workers.

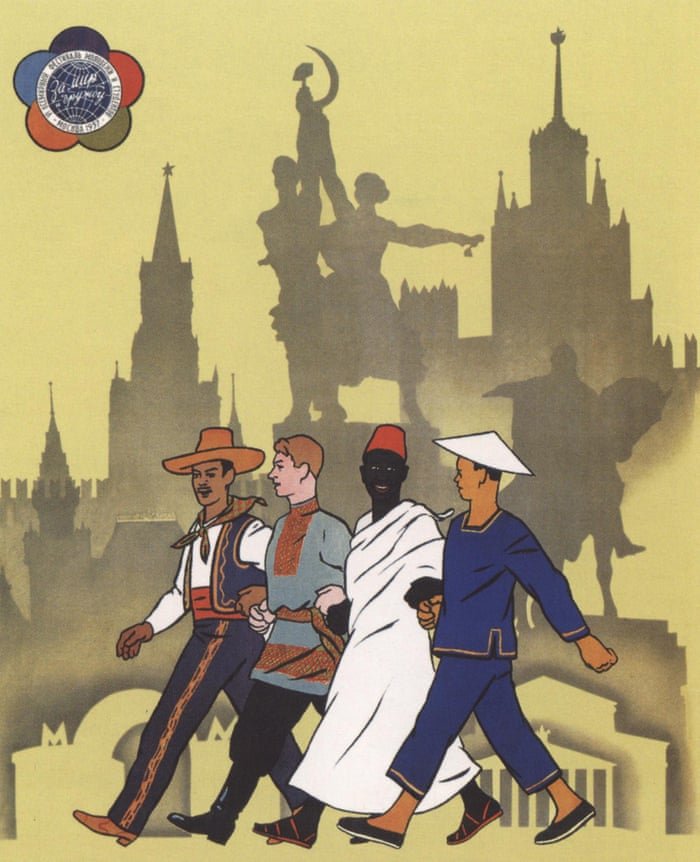

The appeal of American culture (soft power) boosts foreign policy. Some of the best examples occurred during the Cold War. In 1959, Vice President Richard Nixon engaged Nikita Khrushchev in the “Kitchen Debates” at the American National Exhibition in Moscow. In a model home with the newest American conveniences, including a washing machine, microwave, and electric stove, Nixon touted the benefits of living under a capitalist system.

Soft power is often best wielded by non-political actors. In 1956, the State Department initiated a program of jazz ambassadors to bring the appeal of American music and culture around the globe. Dizzy Gillespie and his integrated band conducted an eight-week tour with stops in Europe, Asia, and South America. Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Benny Goodman went on similar tours to “project an image of interracial harmony abroad.”

It is worth noting, this process worked in reverse too. The Soviet Union used Jim Crow laws to undermine claims about the superiority of American democracy by demonstrating the inconsistencies between “all men are created equal” and racial segregation. To read more about this fight, I highly recommend Cold War, Civil Rights by Mary Dudziak.

While the twentieth century is when American soft power was at its apex, it started that process two decades earlier. The Declaration of Independence was the original export of soft power. The promises of liberty and equality inspired generations of revolutions across the globe. Revolutionaries in France, Haiti, South America, and Eastern Europe quoted Thomas Jefferson, and not by accident.

After the revolution, generations of immigrants came to the United States to start a new life, dreaming of better opportunities, the chance to own land and support a family, and most of all, a fresh start. Sometimes it was immigrants landing in San Francisco, eager to find their gold nugget and a life of riches. Other times it was waves of Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants passing through Ellis Island.

The American dream is soft power.

Much like our norms, customs, and institutions, we take soft power for granted. We don’t see it every day or track its price at the gas station. It can feel intangible. That’s the catch with these valuable things that strengthen our nation and our economy; they often take a long time to build up. And like so many valuable things, soft power is much easier to destroy than to build.